Trip to the Art Party Conference in Scarborough

Posted: November 25, 2013 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: art, art education, Art Party Conference, Basic Design, Bob and Roberta Smith, Chelsea School of Art, Frederick Brill, Patrick Brill, Pictures for Schools, Scarborough Leave a comment Although my project is historically focused, I’m also interested in how an understanding of the aims, ideals and achievements of Pictures for Schools, and the post-war economic, social and political climate in which it took place, can add to discussion about the nature and function art education today, particularly as it seems that subjects with a creative focus are currently being marginalised in favour of more conventional academic subjects under the recently-introduced English Baccalaureate (for press coverage of these concerns, written by artists among others, see www.theguardian.com/education/2012/nov/02/arts-leaders-concerns-ebacc-schools).

Although my project is historically focused, I’m also interested in how an understanding of the aims, ideals and achievements of Pictures for Schools, and the post-war economic, social and political climate in which it took place, can add to discussion about the nature and function art education today, particularly as it seems that subjects with a creative focus are currently being marginalised in favour of more conventional academic subjects under the recently-introduced English Baccalaureate (for press coverage of these concerns, written by artists among others, see www.theguardian.com/education/2012/nov/02/arts-leaders-concerns-ebacc-schools).

This weekend I attended the Art Party Conference in Scarborough, an event initiated by artist Bob and Roberta Smith (real name Patrick Brill: it turns out that Brill’s father, Frederick Brill, a Principal of Chelsea College of Art in the 1960s and 1970s, had paintings in Pictures for Schools, demonstrating how widespread contributors to Pictures for Schools were in the post-war art world and educational hierarchy). The event aimed to offer a non-political take on the conventional political party conference format, bringing together artists, educators, students and others with an interest in the arts and arts education to celebrate, discuss and share approaches to art and art education, and to demonstrate and argue the value of arts and creativity in education and society.

This weekend I attended the Art Party Conference in Scarborough, an event initiated by artist Bob and Roberta Smith (real name Patrick Brill: it turns out that Brill’s father, Frederick Brill, a Principal of Chelsea College of Art in the 1960s and 1970s, had paintings in Pictures for Schools, demonstrating how widespread contributors to Pictures for Schools were in the post-war art world and educational hierarchy). The event aimed to offer a non-political take on the conventional political party conference format, bringing together artists, educators, students and others with an interest in the arts and arts education to celebrate, discuss and share approaches to art and art education, and to demonstrate and argue the value of arts and creativity in education and society.

As I realised when I read editions of the Society for Education in Art’s journal Athene dating back to 1930s and 1940s, these same debates have been going on for decades and the fact that these issues are still being debated adds to my uncertainty that schemes like Pictures for Schools had any kind of lasting or widespread impact; although Pictures for Schools appears to have achieved a relative degree of success at the time (in terms of the exhibitions themselves, although it’s harder to gauge their impact at a student/school level), today it’s all but forgotten about and it appears all too easy for such well-intended initiatives in arts education to fall victim to politics, lack of funding and lack of enthusiasm at governmental, county and school levels.

The Art Party Conference, which spread out across the vast, grand Scarborough Spa complex, was filled with talks, performances, film screenings and hands-on art activities, as well as discussions around the nature, value and importance of art and art education. Organisations related to art, education and the development and support of artists had stalls and activities on offer, including Yorkshire Sculpture Park and the National Arts Education Archive, alongside the National Society for Education in Art and Design; the NSEAD grew out of the Society for Education in Art, which administered Pictures for Schools and I asked current General Secretary Lesley Butterworth if she knew much about the scheme – she was aware of it, and what’s more her husband, artist John Butterworth, contributed artworks to it. However, discussion of historical precedents in art education was largely lacking.

The one speaker who I did hear reference examples of important events, shifts and initiatives in art education historically was Mark Hudson, son of Basic Design education pioneer Tom Hudson and curator of the recent Transitions exhibition about Hudson’s work and legacy at Yorkshire Sculpture Park, who briefly talked about the choice of Scarborough as a venue due to its association with an art educational summer school run by Victor Pasmore, Hudson, Richard Hamilton and others in 1959. He explained that at the time ‘most people involved in art education still hoped modern art would blow over’, and that the organisers of the summer school believed that ‘art is fundamental to society and that if you don’t understand the art of your own time you aren’t really participating in the world around you’. Although Basic Design relates to higher education, and in particular the development of the art foundation course, this idea that art helps you participate in the world around you is something that is key to my understanding of the aims of Pictures for Schools.

In the same series of discussions, around why art is important and how it should be taught in schools, Manchester-based artist Professor Pavel Büchler, in one sentence, said something which I thought was more relevant and insightful than most of the other speakers put together, which is that art teaching should include teaching how children to look and how to see (I find that all too often speakers come with their own pre-prepared soundbites which bear no relation to the subject actually under discussion, and whilst Richard Wentworth was entertaining and made a couple of interesting points about art being part of how we conduct ourselves and who we are, he mainly rambled on at complete divergence to the rest of the discussion). In the discussion on how art should be taught in schools, Sheila McGregor of Axisweb made the valid point that art should be valued for its ability to develop problem-solving and thinking skills and ideas, and she also argued for access to an expanded art historical cannon and the work of living artists in art galleries, both things it would be hard to have any argument with. However, I fundamentally disagreed with her assertion that creativity is a highly specific, rather than cross-curricular, skill (see my points below in answer to Bob and Roberta Smith about the importance of art*) and was pleased to hear some objections from the audience. Sam Cairns from the Cultural Learning Alliance had an interesting outlook, too, which is that art can help children find their place in the world, and therefore improve both children’s lives and our lives. Although I’m uneasy about the value of art being reduced to economics, and she also argued that art can contribute to economic wellbeing, I was interested in Cairns’ assertion that children who engage in art are three times more likely to vote as adults as one of the aspects of Pictures for Schools I am looking it as how it was seen to contribute to the development of children as citizens.

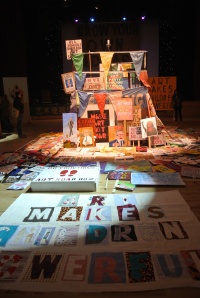

The event which, of course, started with a march, was full of signs and placards with slogans like ‘Art makes children powerful’ and ‘All schools should be art schools’, as well as a plethora of portraits of unpopular Education Secretary Michael Gove. The emphasis was definitely on fun, rather than in-depth conversation, the development of practical, pragmatic strategies for change or serious suggestions to influence those with the capacity to make changes at a governmental level. Humour was often used to get the message across, from a ‘Goveshy’ which offered opportunities to throw balls at Gove, to an appearance from lookalike ‘Michael Grove MP’ who was booed and hand clapped off the podium.

The conference was fun, thought-provoking, interesting, stimulating, talkative and tiring, but in many ways it felt like it was preaching to the converted. It would be good, therefore, if future events and activities could build on this starting point and engage with even more people, not just those already active in the art scene. One thing which I felt was noticeably absent was the voices of those the conference was aimed at – children, teachers and students of art themselves – and I also thought that the conference relied too much on the opinions of big-name artists. Hopefully, however, the event will have showed that there is a critical mass of those who believe art is something important and worth prioritising in education.

The conference was fun, thought-provoking, interesting, stimulating, talkative and tiring, but in many ways it felt like it was preaching to the converted. It would be good, therefore, if future events and activities could build on this starting point and engage with even more people, not just those already active in the art scene. One thing which I felt was noticeably absent was the voices of those the conference was aimed at – children, teachers and students of art themselves – and I also thought that the conference relied too much on the opinions of big-name artists. Hopefully, however, the event will have showed that there is a critical mass of those who believe art is something important and worth prioritising in education.

* In the run-up to the conference Bob and Roberta Smith posed ‘three vital questions’ to the public, ‘What first turned you onto art? How do you think art should be taught in schools? Why do you think art is important?’, and I spent a lot of time mulling them over before the event and coming up with some personal responses which were informed both by my experiences and by thoughts I’ve been having about the reading I’ve been doing since I started this project (see answers below).

Answers to Bob and Roberta Smith’s questions

What first turned you onto art?

I’ve been trying to think back to the first time I became conscious of art, and realised that I can’t actually remember a time when I wasn’t ‘turned onto’ art. What I did remember, though, was the first time I can remember being actively aware of art, and realising that it was something important to me. My first memory of art is also one my earliest memories, and it must date back to when I was about three or four. I remember that one day at nursery I painted a picture and I was really proud of it. I can still remember how good it felt to have created something which seemed like it came out of me and showed everyone else how I felt and saw things. Our pictures were then all displayed somewhere to dry until home time and I couldn’t wait for my mum to come and collect me so I could show her my painting. However, when it came to taking our pictures home another child picked up mine and tried to take it! I remember feeling a really strong sense of injustice that someone else was trying to take what was mine and what I had made and was unique to me. I didn’t understand how they could possibly try and appropriate it as theirs when it quite clearly showed my individual way of expressing things, and found it incomprehensible that other people wouldn’t believe it was mine. I remonstrated with the nursery teacher, but the other child refused to budge and insisted it was theirs. I don’t remember what the outcome was, but I suspect neither of us ended up getting to take the picture home. It might seem like an insignificant incident but I still remember feeling incredibly strong emotions about it.

So this is part of why I think art is important – this expressive and communicative function. And this brings me in a roundabout way into how I think art should be taught in schools …

How do you think art should be taught in schools/why do you think art is important?

When I was a child ‘artist’ was one of several things (see also ‘pop star’, ‘newspaper editor’) I wanted to be when I grew up. First I thought I would be a painter and then, when I got into my teens, a Pop Artist or installation artist. This was probably because at school art was something I felt good doing, or that I felt I did with a relative degree of effectiveness. Although I didn’t become a painter or fine artist, I don’t regard studying art at school as a waste of time as I still feel like having the chance to be artistic when I was younger was really important to my development and the way I see and approach the world now.

This brings me to some of the reading I’ve been doing lately. An important figure so far has been Herbert Read, and the basic premise of his 1943 book Education Through Art is that the purpose of education is the creation of artists and that art is fundamental to society. It’s his definition of artist which really interests me, as he didn’t mean artist in the narrow sense that we often think of artists, and he didn’t think that an artist was a special kind of person who was different to everyone else. He thought that being artistic meant taking a creative approach to life and creating ‘art’ in (and applying certain standards of craft to) everything you did; he saw art as an approach which could be applied to whatever trade or career the child eventually took up. This idea that everyone is an artist was also a slogan strongly associated with Joseph Beuys, another figure who intrigues me, and there’s a very good, concise explanation of his thoughts on art and creativity here.

With regard to teaching art or any other creative subject in schools, I acknowledge that not every child is going to find art (or music or drama) stimulating, interesting, exciting, or relevant to them. I think that what is vital to every person, though, is finding their own, unique way of expressing themselves, which works for them, and finding their niche in the world where they feel at their most confident, comfortable and creative, whether that is through making, writing, cooking, sports, doing scientific experiments, caring, teaching, or whatever else they do. I’d argue that to a certain extent all of these things need approaching with a creative outlook, and that each person will have their own way of looking at them and signature way of doing things. Therefore, I think it’s important that everyone has a chance to have a go at as many different kinds of expression and ways of learning, including art and creative expression, as possible in schools, to have a chance to find out what’s their best way of communicating and exploring the world around them, and to understand that their way of communicating and expressing themselves is just one among many potential ways.

One important aspect of teaching and learning art is practical and expressive – making things and learning skills and techniques. But I think there’s another really important aspect of art, and therefore need for its teaching in schools, which is its potential to contribute to discussion, conversation and analysis of the world around us. I think it’s really important that art isn’t just taken for granted and seen as something which is remote from people’s lives and fixed in its meaning; I think that art should be a subject of discussion, and fluid in its meaning and interpretations. Art is often regarded as something people don’t understand, especially if they haven’t really grown up with it, and therefore they think it ‘isn’t for people like them’ or they feel they are lacking some particular kind of knowledge which would tell them how to interpret and make meaning of it. I have a (probably optimistic/utopian) outlook which makes me think there is no reason why art should not be something people are as confident visiting for entertainment, and discussing and articulating an opinion on, as the latest reality TV show, popular novel, film franchise, food/diet/exercise craze or whatever, we just need to get rid of this perception that art is somehow elevated above the rest of life.

Ideally, to help with this, I think schools should take children to art exhibitions (or even, as in the case of Pictures for Schools, have original works of art in school themselves, although this is increasingly problematic for all sort of bureaucratic and financial reasons). This should be followed up by making sure the children discuss what they’ve seen in a meaningful way which involves them analysing what it is about particular artworks which make them interesting or exciting to them, or considering why some artworks weren’t effective and why some artworks are more successful and engaging than others. Rather than being simply taught or told about artworks by the teacher, and what they are meant to ‘mean’, therefore, I think children should be encouraged to see artworks with their own eyes and think about them for themselves (see Susan Sontag’s early ’60s essay collection Against Interpretation, where she rails against the overintellectualism of the way art is presented in society, for example by critics, and calls for people to rediscover and trust their own sensory reactions to things rather than feeling like art can only by valued for what it ‘says’ rather than it inherently ‘is’ or ‘does’). Although being taught about key moments, styles and forms, and being shown examples of these from art history, can help put artworks in context, I think it’s really important that children are also encouraged to develop their own opinions on art, and to say what they really see and think. By discussing and challenging these opinions, children could gain skills and confidence in talking about and interpreting art – as well as about anything else they encounter in the world around them.

In an ideal world, I think all schools should be near enough to make a visit to a gallery to see art first-hand. Luckily, there was a really good local art gallery within walking distance of my school, where we went on school trips to see the foundation shows of the county art college, which toured to a few local venues, as well as solo shows by established and up-and-coming artists. I particularly remember that Sophie Ryder filled the Victorian gallery spaces with casts of hares, and the repeated imagery of the strange, slightly-grotesque hares made a huge impression on me both visually and intellectually. Sadly, the Metropole gallery closed down soon after I moved away to university, and it worries me that it’s becoming harder, not easier, to see art unless you already have the interest, determination and means to seek it out, which can only contribute to the idea that it is a luxury and not an essential part of life.