The LCC and the Arts I: The Open-Air Sculpture Exhibitions

Posted: July 21, 2015 Filed under: Uncategorized Leave a commentIf we remember 1945 at all – and it seems, sadly, an increasingly distant memory – we remember it for its principles of a free and national health service, a system of social security (not ‘welfare’ or ‘benefits’) in which a common duty to share burdens and support the less fortunate was almost universally accepted, and for the seemingly radical idea that the economy should be the people’s servant, not their master.

But beyond this – as if those values were not sufficiently remarkable by contemporary standards – there was a belief in a democratic and shared civic culture. The arts were understood as an integral part of this.

Labour’s 1945 manifesto, ‘Let Us Face the Future’ (modestly described as ‘A Declaration of Labour Policy for the Consideration of the Nation’), urged that:

National and local authorities should co-operate to enable people to enjoy their leisure to the full, to…

View original post 1,260 more words

Barkingside: visiting the suburbs

Posted: July 20, 2015 Filed under: Uncategorized Leave a commentMy response to the recent visit to Barkingside as part of the London workshop of the Modern Futures network.

Exhibition visit: We Want People Who Can Draw: Instruction and Dissent in the British Art School, Manchester Metropolitan University Special Collections (until 31 July)

Posted: July 16, 2015 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: archives, art, art education, Art school, dissent, Education, Exhibition catalogue, exhibitions, Hornsey, Manchester, Manchester Metropolitan University, occupations, post-war, protest, universities Leave a commentThough it’s not directly related to schools, as part of the contextual reading for my PhD I have also read a lot about the history and development of art education, specifically art schools and colleges in Britain, from the municipal colleges of art that were set up in industrial towns and cities in the nineteenth century, to the changing status of provincial schools of art and art degrees following the Coldstream Report of 1960, to the student protests and occupations sparked by that at Hornsey in 1968, where students demanded more say in the direction of their education.

The current exhibition at Manchester Metropolitan University’s Special Collections brings together an impressive, stimulating and inspiring range of materials relating to the last of these aspects of the history of British art education, borrowed from individuals and institutions including the Women’s Art Library in London. They encompass manifestos, books, magazines, pamphlets and student journals, including material from Art & Language in Coventry and King Mob at Goldsmiths in London, along with exhibition publicity, films, some evocative photographs of demonstrations and occupations, and prints and posters relating to these demonstrations, and correspondence between students and university officials. Through these artefacts, the exhibition draws out links with wider and international movements for change such as the Situationist International and radical feminism. Many of the publications were amassed and distributed by Ron Hunt, the librarian at Newcastle University, who must have some tales to tell!

Many of the objects, as well as being fascinating documents of the time and a particular educational and social moment, raised important questions about the purpose and uses of art in the post-war context, a period in which the government and other authorities had started by promoting the potential and responsibility of art to take on an explicitly social role in both educating and improving the lives and leisure of the masses. Should art, and the critical and technical skills students developed at art schools, be used for the good of society, as in the street theatre workshops discussed in the exhibition, or should it be enlisted into the commercial services of advertising, against which students at Hornsey were partly protesting? One of the most intriguing items in this regard was Ken Garland’s 1964 First Things First manifesto, recently updated fifty years on, which enlisted the signatures of several designers to rail against advertising and call for design which worked for the public good. It would be interesting to know what came of the signatories, and where their future careers led them …

At a time when the value – and cost – of studying arts subjects, not just at school but at degree level, is being questioned, and when university buildings are still being occupied through student protests, it was strange not to see present-day imagery and examples in the exhibition, despite this providing the starting point for the exhibition catalogue.

The catalogue is well worth a read and is accessible as PDF at www.specialcollections.mmu.ac.uk/files/wewantpeople_guide.pdf.

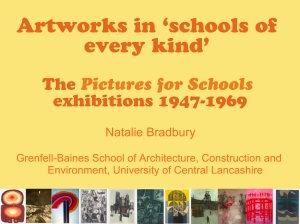

Reflections on Pictures for Schools paper at International Conference of Historical Geographers, London

Posted: July 7, 2015 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: art, conferences, events, geography, historical geography, ICHG, International Conference of Historical Geographers, London, Nan Youngman, Pictures for Schools, post-war, presentations, reconstruction, research, RGS-IBG Leave a comment My presentation at this year’s International Conference of Historical Geographers at the Royal Geographical Society was a step up from last year’s RGS-IBG summer conference. Whereas last year I presented a particular aspect of my PhD research on Pictures for Schools in a general session for post-graduates to share their ongoing research, this time I was invited to be one of five speakers contributing to a session themed ‘Making post-war Britain: Mobility, planning and the modern nation’.

My presentation at this year’s International Conference of Historical Geographers at the Royal Geographical Society was a step up from last year’s RGS-IBG summer conference. Whereas last year I presented a particular aspect of my PhD research on Pictures for Schools in a general session for post-graduates to share their ongoing research, this time I was invited to be one of five speakers contributing to a session themed ‘Making post-war Britain: Mobility, planning and the modern nation’.

Papers explored research already undertaken as well as projects in their early stages. My Director of Studies, Hannah Neate, chaired the session, linking each paper through pointing out shared themes and overlaps. Papers included Ruth Craggs on returning colonial administrators, co-written with Hannah. This attempted to direct attention away from a focus on the often-told national and domestic story towards wider international motilities and geopolitical shifts and changes, as told through the figure of one administrator, RW Phelps, as part of a bigger picture of people such as architects and planners. Ian R. Cook then spoke engagingly on post-war planners’ organised study tours abroad, and the way in which certain organisations shaped the way in which planners and policy-makers thought about post war development. Heike Jons’ work on the location and development of post-war universities was well-illustrated with maps and diagrammes. Finally, Ben Rogaly presented his ongoing work with Rebecca Taylor on the experiences of strangeness and belonging in post-war new towns, and the way in which communities were unsettled in the 1950s and 1960s due to building and redevelopment and large-scale migration from places such as London to new and expanding towns such as Peterborough.

As ever, it was hard to narrow down the focus of my research to fit a fifteen-minute slot, but I attempted to convey something of the story of the Pictures for Schools exhibitions and the way in which they aimed at – and succeeded in – distributing original artworks to not just schools but to county councils, education authorities, universities (including Imperial College, where the session took place!) and teacher training colleges across the country. My presentation was led heavily by the use of visuals and archival finds such as exhibition posters and photographs of visitors to the exhibitions, as well as a selection of representative artworks purchased by educational buyers, offering an opportunity to revisit and make use of material I hadn’t yet highlighted elsewhere. The visuals received particularly positive conference from members of the audience, unsurprisingly, particularly a series of 1960s posters advertising the exhibitions. I was also keen to demonstrate that, although Pictures for Schools was enabled by specific post-war developments such as the post-war school building programme, the formation and support of the Arts Council and Ministry of Education endorsement of the role of the arts in schools, it operated autonomously of the state and was driven by the ideas, values and experience of its founder, the painter and teacher Nan Youngman. I aimed to show how Pictures for Schools benefited particularly from the support and engagement of networks of geographically dispersed artists and organisations Youngman encountered both in her dual career as an educationalist and a painter, and in her social life, and to suggest that I have experienced the value of biographical approaches in historical geographical research.

The panel format for taking questions meant that unfortunately I wasn’t asked any questions in detail – beyond whether there was any measurement of the impact and engagement of the artworks sold through Pictures for Schools. I answered that the exhibitions must be understood on more than one level – firstly, engagement with artworks at the exhibitions themselves, by visitors to the exhibitions, which was measured to some extent through questionnaires and voting boxes, and secondly the life of the artworks once they had left the exhibitions, which strangely did not seem to be of interest to the organisers. Some interesting questions were put to the panel, including: whether it was possible to see any specific outcomes of the influences of study tours abroad on post-war British planning; the apparent tensions between a time in Britain’s history generally regarded as being dominated by leftist welfare statism, and the fact that people such as returning colonial administrators were often part of a more old-fashioned establishment and old boys’ network culture; and what motivated and drove individual reformers such as planners, and whether it was political or ideological or otherwise.

The conference was a great chance to hear from people who’d been at the previous talk I did and said I’d made interesting progress, both in my research and presentation and in the discussion of my findings. It was also great to meet researchers, elsewhere at the conference, who were interested in related figures and ideas, from Henry Morris, Director of Education in Cambridgeshire and founder of the county’s village colleges (who employed Youngman as a peripatetic art adviser from 1944-1954, travelling around these colleges as well as other rural schools), an influence highlighted in my presentation, to the Rosc exhibitions in 1960s Ireland, which I was told about by another delegate.

I also enjoyed the plenary from Catherine Hall, historian at UCL, on slavery and freedom, which touched on not just the ways in which the fields of history and historical geography inform and are informed by one another, but showed how historical research can frame and be framed by contemporary issues and discourses, in this case the construction and perception of race in society, though economics, society and culture.

Finally, I was pleased to receive a bursary from the Historical Geography Research Group covering half the price of my ticket, which assisted greatly in covering my conference expenses.