Guest blog post on Revolutionary Red Tape

Posted: May 4, 2020 Filed under: post-war | Tags: art, Artists International Association, loan collections, Nan Youngman, Painters, painting, Pictures for Schools, public art, schools, women Leave a commentThanks to Dr Emma West for inviting me to write a guest blog post about Pictures for Schools founder Nan Youngman for her research blog Revolutionary Red Tape, as part of ‘Advocates for the Arts’, a series about pioneering women. Emma is currently undertaking an enviable post-doc at Birmingham University focusing on culture in public places in twentieth-century Britain.

Read my blog post online here: https://emmawest.art.blog/2020/05/04/advocates-for-the-arts-nan-youngman/

Exhibition visit: Out of the Crate, Manchester Art Gallery

Posted: January 31, 2020 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: art, collections, Education, exhibitions, loan collections, Manchester, Manchester Art Gallery, Pictures for Schools, schools, sculpture Leave a comment Following hot on the heels of But What If We Tried? at Touchstones, Rochdale in 2019, which attempted to display the entirety of the borough’s publicly owned art collection at once, Manchester Art Gallery is offering an insight into its sculpture stores (only 3 per cent of the collection is usually on display at any one time). About 25 per cent can be seen in the current exhibition, Out of the Crate, which explores and highlights how the work came to be in the collection and asks for information about some of the work (it’s not always clear who the work is by or how it got there!).

Following hot on the heels of But What If We Tried? at Touchstones, Rochdale in 2019, which attempted to display the entirety of the borough’s publicly owned art collection at once, Manchester Art Gallery is offering an insight into its sculpture stores (only 3 per cent of the collection is usually on display at any one time). About 25 per cent can be seen in the current exhibition, Out of the Crate, which explores and highlights how the work came to be in the collection and asks for information about some of the work (it’s not always clear who the work is by or how it got there!).

Many of Britain’s best-known nineteenth, twentieth century and contemporary sculptors are represented in the collection, working across a variety of styles and media, from portraiture to modernism. My favourite piece was ‘Rocking Chair No. 4’ (1950), a tiny bronze sculpture by Henry Moore, which was bequeathed to the gallery in 2012 by Harry M Fairhurst, architect of the UMIST campus and the renowned Hollaway Wall. Freeze-framing a small moment of familiar tenderness, but blurring both human and animal forms, its intimate scale made me long to pick it up and handle it and see if it actually rocked!

Many of Britain’s best-known nineteenth, twentieth century and contemporary sculptors are represented in the collection, working across a variety of styles and media, from portraiture to modernism. My favourite piece was ‘Rocking Chair No. 4’ (1950), a tiny bronze sculpture by Henry Moore, which was bequeathed to the gallery in 2012 by Harry M Fairhurst, architect of the UMIST campus and the renowned Hollaway Wall. Freeze-framing a small moment of familiar tenderness, but blurring both human and animal forms, its intimate scale made me long to pick it up and handle it and see if it actually rocked!

Some of the sculptures in the collection had been purchased for educational purposes, from the Horsfall Art Museum, which aimed to bring beauty to industrial Ancoats, to pieces from the Rutherston Loan Collection (now accessioned into the main collection) which was established in the 1920s to lend work to schools and educational establishments in the north of England.

Some of the sculptures in the collection had been purchased for educational purposes, from the Horsfall Art Museum, which aimed to bring beauty to industrial Ancoats, to pieces from the Rutherston Loan Collection (now accessioned into the main collection) which was established in the 1920s to lend work to schools and educational establishments in the north of England.

Although this scheme is no longer in operation, one of the most interesting aspects of the exhibition is documentation of a project involving a group of boys from Burnage Academy, who were asked to choose a sculpture to display in their school for a day via Art UK’s ‘Masterpieces in Schools’ initiative. Just as Pictures for Schools aimed to ask searching questions of child visitors through the provision of questionnaires about the exhibitions, and to encourage them to see themselves as patrons of art, the students were encouraged to look critically at the artworks, how they were made and what they represented, as well as to think about the role of a curator. It was fascinating to read their rationale about what would stimulate discussion and what their peers would find interesting, and the types of questions they asked of the work, such as “Is the paper ball an actual sculpture?” (their eventual choice of ‘Cobra’, a 1925 sculpture by Jean Demand, narrowly beat Martin Creed’s conceptual ‘Work No 88: A Sheet of A4 Paper Crumpled Into A Ball’).

Out of the Crate is at Manchester Art Gallery until Sunday 28 November 2021: https://manchesterartgallery.org/exhibitions-and-events/exhibition/out-of-the-crate/

Out of the Crate is at Manchester Art Gallery until Sunday 28 November 2021: https://manchesterartgallery.org/exhibitions-and-events/exhibition/out-of-the-crate/

Chandigarh College of Art, India

Posted: December 1, 2019 Filed under: post-war | Tags: architecture, art, art education, Art school, buildings, Chandigarh, Education, India, new towns Leave a commentArtworks from the Hertfordshire school loan collection on Inexpensive Progress

Posted: November 29, 2019 Filed under: post-war | Tags: art, art education, collections, Education, Hertfordshire, loan collections, Painters, painting, Pictures for Schools, prints, schools Leave a commentThe writer and collector Robjn Cantus has posted a really interesting blog about works in his collection which he purchased from the sale of the Hertfordshire County Collection; several pieces were purchased from Pictures for Schools, including prints by Alistair Grant, Michael Rothenstein and Julia Ball. It’s great to find out more about the biographies of the artists, some of whom I have heard of but many who are new to me.

Read the post at https://inexpensiveprogress.com/post/189340044940/my-pictures-for-schools-hertfordshire.

Visit to the University of Loughborough art collection

Posted: November 24, 2019 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: Abstract art, art, collections, John Piper, Leicestershire, painting, Peter Peri, Pictures for Schools, post-war, prints, public art, sculpture, Stewart Mason, teacher training, universities, University of Loughborough, Willi Soukop Leave a comment Last month I spent a very pleasant early autumn afternoon wandering around Loughborough University’s sprawling campus, guided by a map of its extensive sculpture collection.

Last month I spent a very pleasant early autumn afternoon wandering around Loughborough University’s sprawling campus, guided by a map of its extensive sculpture collection.

Loughborough is a market town in Leicestershire – a county that, under longstanding Director of Education Stewart Mason, embraced patronage of the arts in educational settings in the post-war period in a big way. As well as purchasing and commissioning site-specific works for individual schools, Leicestershire’s loan collection was one of the largest in the country, and purchased artworks from Pictures for Schools among other sources. Mason advised and guided Loughborough University on some of its purchases, and his influence in the county is acknowledged in the Stewart Mason building on campus.

The university’s sculpture collection punctuates the sports grounds that dominate the campus (Loughborough has a reputation for attracting sporty students). Given university status in 1966, the campus architecture has a strong modernist feel, although it’s undergone significant expansion since then. Known as Loughborough University of Technology until 1996, there’s a strong theme of science and technology in many of the artworks, particularly around the science buildings, which feature a number of steel artworks by Paul Wagner. There was also a tradition of students producing their own furniture, much of which is still in use around campus.

The university’s sculpture collection punctuates the sports grounds that dominate the campus (Loughborough has a reputation for attracting sporty students). Given university status in 1966, the campus architecture has a strong modernist feel, although it’s undergone significant expansion since then. Known as Loughborough University of Technology until 1996, there’s a strong theme of science and technology in many of the artworks, particularly around the science buildings, which feature a number of steel artworks by Paul Wagner. There was also a tradition of students producing their own furniture, much of which is still in use around campus.

Many well-known and lesser artists of the post-war period are represented on campus, including Willi Soukop, who undertook many commissions for public and educational settings; his Spirit of Adventure, which resembles an aeroplane, is the first artwork encountered on approach to the campus from the town centre, and points the way to a place of learning, discovery and enquiry. Perhaps the most famous sculptor is Lynn Chadwick, whose solemn trio of angular figures The Watchers commemorates three influential figures in the history of the university. However, my favourite artworks were those which were less conspicuous, such as Austin Wright’s kinetic sculpture, nestled in a quiet pond area between two buildings, which resembles a calmly bubbling fountain, and Peter Peri’s Spirit of Technology, a man leaping into the unknown from the side of a student residence dining hall.

Many well-known and lesser artists of the post-war period are represented on campus, including Willi Soukop, who undertook many commissions for public and educational settings; his Spirit of Adventure, which resembles an aeroplane, is the first artwork encountered on approach to the campus from the town centre, and points the way to a place of learning, discovery and enquiry. Perhaps the most famous sculptor is Lynn Chadwick, whose solemn trio of angular figures The Watchers commemorates three influential figures in the history of the university. However, my favourite artworks were those which were less conspicuous, such as Austin Wright’s kinetic sculpture, nestled in a quiet pond area between two buildings, which resembles a calmly bubbling fountain, and Peter Peri’s Spirit of Technology, a man leaping into the unknown from the side of a student residence dining hall.

The sculptures are merely the most public-facing element of a much bigger collection, which includes wall-mounted works such as prints, paintings and textiles, displayed in areas such as boardrooms, corridors and waiting areas. I managed to see a couple of works inside buildings, including prints by Bridget Riley and John Piper, as well as a number of portraits of university grandees which showed their influence on the university.

The sculptures are merely the most public-facing element of a much bigger collection, which includes wall-mounted works such as prints, paintings and textiles, displayed in areas such as boardrooms, corridors and waiting areas. I managed to see a couple of works inside buildings, including prints by Bridget Riley and John Piper, as well as a number of portraits of university grandees which showed their influence on the university.

Loughborough University and the former teacher training college Loughborough Training College, which became part of the university in 1977, both purchased work from Pictures for Schools, although the only one I managed to see was Michael Stokoe’s bold, colourful silkscreen Circles & Stripes.

Loughborough University and the former teacher training college Loughborough Training College, which became part of the university in 1977, both purchased work from Pictures for Schools, although the only one I managed to see was Michael Stokoe’s bold, colourful silkscreen Circles & Stripes.

The collection is not static and continues to evolve, commissioning and acquiring work by students alongside established artists. One of the highlights is one of the most recent works, an interior design scheme by Giles Round for the RADAR office. Alongside furniture and Round’s selection of artworks from the collection, this includes a wallpaper which repeats images of tools from a former catalogue across the walls. Round’s design scheme acts as a subtle reminder of the university’s past and enters into dialogue with work purchased and commissioned during previous eras of the life of the institution.

The collection is not static and continues to evolve, commissioning and acquiring work by students alongside established artists. One of the highlights is one of the most recent works, an interior design scheme by Giles Round for the RADAR office. Alongside furniture and Round’s selection of artworks from the collection, this includes a wallpaper which repeats images of tools from a former catalogue across the walls. Round’s design scheme acts as a subtle reminder of the university’s past and enters into dialogue with work purchased and commissioned during previous eras of the life of the institution.

To find out more about the collection visit https://www.lboro.ac.uk/arts/arts-collection/.

Recommended event: Modernist Society and Paul Mellon event For the People

Posted: November 3, 2019 Filed under: post-war | Tags: art, conferences, design, events, Manchester, modernism, post-war, public art Leave a commentI can’t attend, but very much recommend the symposium For the People, a day focused on modernism and everyday design, which takes place in Manchester on Saturday 9 November. It features Dawn Pereira and Rosamund West talking about the work of William Mitchell, and public art commissioned by the London County Council for the city’s housing estates, among a stellar line-up of speakers.

For more information visit http://modernist-society.org/events/paul-mellon-talks.

Exhibition visit: This Is Just What I Saw, Radar, Loughborough University

Posted: October 5, 2019 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: art, art education, art teaching, Education, Educators, exhibitions, Marion Richardson, Nan Youngman, Pictures for Schools, research, researchers, schools, teacher training, teaching, universities, University of Loughborough 1 Comment Today she is best known for a method of teaching handwriting, but in the interwar years Marion Richardson’s work in the field of child art was well-known. Pictures for Schools founder Nan Youngman undertook teacher training with her at London Day Training College (forerunner of the Institute of Education) and helped her to organise large exhibitions of children’s work. Richardson’s art teaching was focused on developing children’s confidence and powers of self-expression and critique, aiming to train their ‘inner eye’ and ways of looking as much as their technical skills. One way in which she did this was through the ‘visualisation’ method, where children listened to a description of a place or scene and used it as the basis for their own work. In doing so, Richardson hoped to encourage to see pictures in the places around them, even industrial and everyday scenes not conventionally considered picturesque. Richardson also undertook pattern-making and activities such as fabric design with her students and aimed to encourage children to think about how they furnished their homes. She believed children should be exposed to good examples of art and craft, and have opportunities to discuss these and their own work.

Today she is best known for a method of teaching handwriting, but in the interwar years Marion Richardson’s work in the field of child art was well-known. Pictures for Schools founder Nan Youngman undertook teacher training with her at London Day Training College (forerunner of the Institute of Education) and helped her to organise large exhibitions of children’s work. Richardson’s art teaching was focused on developing children’s confidence and powers of self-expression and critique, aiming to train their ‘inner eye’ and ways of looking as much as their technical skills. One way in which she did this was through the ‘visualisation’ method, where children listened to a description of a place or scene and used it as the basis for their own work. In doing so, Richardson hoped to encourage to see pictures in the places around them, even industrial and everyday scenes not conventionally considered picturesque. Richardson also undertook pattern-making and activities such as fabric design with her students and aimed to encourage children to think about how they furnished their homes. She believed children should be exposed to good examples of art and craft, and have opportunities to discuss these and their own work. Richardson died prematurely in 1946, but her work and ideas inspired Youngman’s work throughout the rest of her career. Youngman continued to defend them even when they had become regarded as old-fashioned and were superseded among progressive educationalists in the 1960s in favour of more modern ideas about teaching art.

Richardson died prematurely in 1946, but her work and ideas inspired Youngman’s work throughout the rest of her career. Youngman continued to defend them even when they had become regarded as old-fashioned and were superseded among progressive educationalists in the 1960s in favour of more modern ideas about teaching art. A new installation at Radar in Loughborough, by Berlin-based artist Katarina Hruskova, bears the fruits of an arts-research collaboration with Dr Sarah Mills, Reader in Human Geography at Loughborough University, which involved spending time in the archives at Birmingham City University, where Richardson’s papers are held; the title, This is Just What I Saw, comes from words written on the back of children’s pictures.

A new installation at Radar in Loughborough, by Berlin-based artist Katarina Hruskova, bears the fruits of an arts-research collaboration with Dr Sarah Mills, Reader in Human Geography at Loughborough University, which involved spending time in the archives at Birmingham City University, where Richardson’s papers are held; the title, This is Just What I Saw, comes from words written on the back of children’s pictures. Drawing on aspects of Richardson’s teaching and her students’ work, including visual description, Mills and Hruskova held a series of workshops with young people in schools and other educational settings in the Midlands today. The resulting artworks, on show at Radar, translate images from these children’s work into a trio of colourful carpets. Whilst abstract they’re also suggestive of elements of place and natural forms, such as trees and water. Displayed next to them are condensed versions of the texts which were read to children to inspire the images; in the background plays an audio recording of Hruskova reading these same words, an effect that is both poetic and hypnotic. We’re taken on a journey through first an industrial scene and then a forest, where our attention is drawn to details such as the time of day, the weather around us; our senses can’t help but be aroused, our imaginations fired and our memories taken back to places we’ve known and things we’ve seen.

Drawing on aspects of Richardson’s teaching and her students’ work, including visual description, Mills and Hruskova held a series of workshops with young people in schools and other educational settings in the Midlands today. The resulting artworks, on show at Radar, translate images from these children’s work into a trio of colourful carpets. Whilst abstract they’re also suggestive of elements of place and natural forms, such as trees and water. Displayed next to them are condensed versions of the texts which were read to children to inspire the images; in the background plays an audio recording of Hruskova reading these same words, an effect that is both poetic and hypnotic. We’re taken on a journey through first an industrial scene and then a forest, where our attention is drawn to details such as the time of day, the weather around us; our senses can’t help but be aroused, our imaginations fired and our memories taken back to places we’ve known and things we’ve seen. Alongside this is a small selection of images giving a glimpse into Richardson’s own classroom, and her students’ art practice. Whilst in some ways these images appear formal by today’s standards, with children seated at rows of wooden desks, the children are surrounded by their own pictures and patterns, which hang on the walls, giving an impression of a visually rich and engaging environment.

Alongside this is a small selection of images giving a glimpse into Richardson’s own classroom, and her students’ art practice. Whilst in some ways these images appear formal by today’s standards, with children seated at rows of wooden desks, the children are surrounded by their own pictures and patterns, which hang on the walls, giving an impression of a visually rich and engaging environment. Ideas about childhood, and the nature and purpose of schooling, education and even art have changed considerably since Richardson’s day. By reimagining and reanimating the ideas of this forgotten educationalist, Mills and Hruskova have brought the art teaching of the past powerfully into dialogue with children’s education and experiences today, showing the potential of words and images to inspire creativity and make us look again at how and what we see in the world around us.

Ideas about childhood, and the nature and purpose of schooling, education and even art have changed considerably since Richardson’s day. By reimagining and reanimating the ideas of this forgotten educationalist, Mills and Hruskova have brought the art teaching of the past powerfully into dialogue with children’s education and experiences today, showing the potential of words and images to inspire creativity and make us look again at how and what we see in the world around us.

This Is Just What I Saw is at the Martin Hall Exhibition Space, Loughborough until Friday 25 October: https://radar.lboro.ac.uk/events/this-is-just-what-i-saw-exhibition/

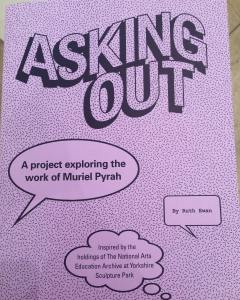

Exhibition visit: Ruth Ewan – Asking Out, Longside Gallery, Yorkshire Sculpture Park

Posted: October 1, 2019 Filed under: post-war | Tags: archives, art, art education, art teaching, craft, design, Education, Educators, exhibitions, installation art, Oscar Murillo, Ruth Ewan, School, schools, teaching, West Riding of Yorkshire, West Yorkshire, Yorkshire, Yorkshire Sculpture Park Leave a comment Working across a variety of media to explore historical narratives and representations, and bring to light untold figures and stories, Ruth Ewan has long been one of my favourite contemporary artists. I was very excited, therefore, when I heard she had been working with the National Arts Education Archive to develop new work for a show at Yorkshire Sculpture Park.

Working across a variety of media to explore historical narratives and representations, and bring to light untold figures and stories, Ruth Ewan has long been one of my favourite contemporary artists. I was very excited, therefore, when I heard she had been working with the National Arts Education Archive to develop new work for a show at Yorkshire Sculpture Park.

Asking Out is an installation in the Longside Gallery which explores the work of Muriel Pyrah, an untrained teacher in Airedale Middle School in Castleford. Whilst Pyrah was not necessarily immersed in the latest ideas about teaching, appearing to base her work on her own experiences of teaching and ideas about students’ needs in the classroom, her work fitted with the progressive agenda of the West Riding Education Authority, who celebrated and promoted her ideas as an example of then-fashionable modes of non-hierarchical, child-centred learning which encompassed learning through doing and direct experience.

The exhibition takes as its starting point the concept of ‘asking out’: Pyrah’s students were required to contribute verbally to her classroom, to articulate their work and ideas, to ask questions and to critique each other’s work. From a relatively deprived town in the Yorkshire coalfield, Pyrah’s students were taken out to explore the world beyond the classroom – into local streetscapes, landscapes and industries, further afield to sites of historical interest and even to London. The aim was to develop confidence in Pyrah’s students, both in themselves and their surroundings. We can see this for ourselves in a set of films made in the early 1970s, towards the end of Pyrah’s career, when the cameras were invited into the classroom in order to share Pyrah’s work, and observe discussions among the children about what they’d seen, learned and experienced. The students appear lively and engaged, if sometimes a little awkwardly formal.

The aim was to develop confidence in Pyrah’s students, both in themselves and their surroundings. We can see this for ourselves in a set of films made in the early 1970s, towards the end of Pyrah’s career, when the cameras were invited into the classroom in order to share Pyrah’s work, and observe discussions among the children about what they’d seen, learned and experienced. The students appear lively and engaged, if sometimes a little awkwardly formal. An accompanying publication to Asking Out, containing essays and interviews with some of Pyrah’s former students, complicates the narrative, suggesting that her unorthodox methods did not work for or include everyone. Whilst some students thrived from being expected to talk in front of the class others, perhaps unsurprisingly, found the experience difficult and stressful. Pyrah also appeared to have very particular ideas about the ‘correct’ way of talking; use of local dialect was discouraged, adding to a sense of distance from other students in the school.

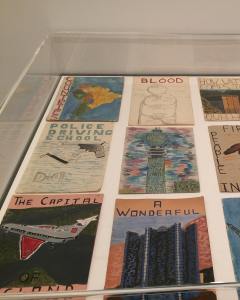

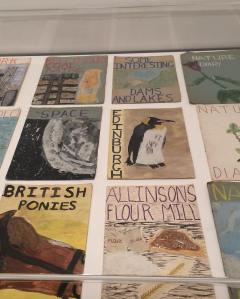

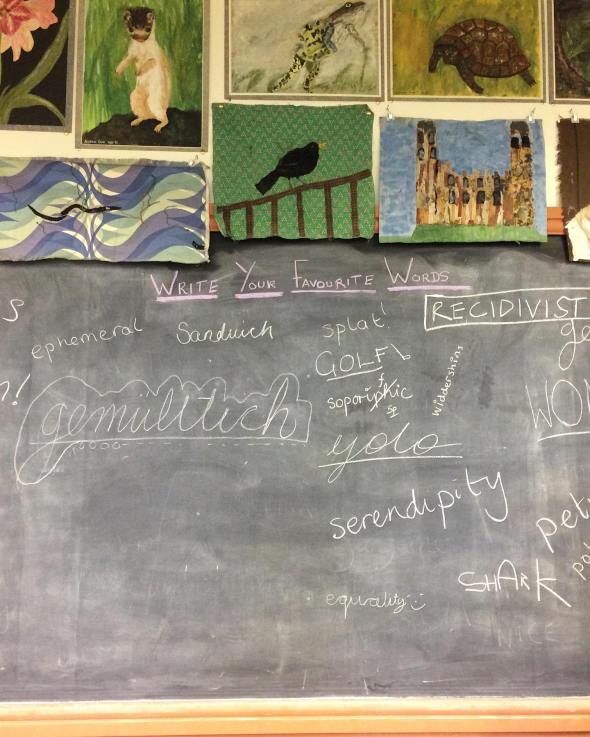

An accompanying publication to Asking Out, containing essays and interviews with some of Pyrah’s former students, complicates the narrative, suggesting that her unorthodox methods did not work for or include everyone. Whilst some students thrived from being expected to talk in front of the class others, perhaps unsurprisingly, found the experience difficult and stressful. Pyrah also appeared to have very particular ideas about the ‘correct’ way of talking; use of local dialect was discouraged, adding to a sense of distance from other students in the school. Ewan has reactivated and brought to life Pyrah’s ideas, asking us to experience them for ourselves and inviting visitors to participate in and contribute to a reconstruction of her 1970s classroom. The overall impression is stimulating and colourful: the eye is constantly drawn towards text and images. As well as familiar wooden schooldesks, the room is full of artefacts to explore: a piano and songbooks; a nature table, full of tactile objects; maps and photographs showing features of the landscape; books and posters about how everyday goods are made; and a blackboard for writing, sharing and learning the meaning of interesting, unusual, difficult and favourite words.

Ewan has reactivated and brought to life Pyrah’s ideas, asking us to experience them for ourselves and inviting visitors to participate in and contribute to a reconstruction of her 1970s classroom. The overall impression is stimulating and colourful: the eye is constantly drawn towards text and images. As well as familiar wooden schooldesks, the room is full of artefacts to explore: a piano and songbooks; a nature table, full of tactile objects; maps and photographs showing features of the landscape; books and posters about how everyday goods are made; and a blackboard for writing, sharing and learning the meaning of interesting, unusual, difficult and favourite words. Above all, what comes across is the sense that the children were encouraged to look. Much of the children’s work, hung up around the classroom, is based on close and careful observation – of nature, of places, of the effect of the seasons.

Above all, what comes across is the sense that the children were encouraged to look. Much of the children’s work, hung up around the classroom, is based on close and careful observation – of nature, of places, of the effect of the seasons. These historical artefacts are given added poignancy and power through their proximity to another installation encouraging, prioritising and revealing children’s ways of seeing. Frequencies by Colombian artist Oscar Murillo – who is currently nominated for the Turner Prize – brings together canvases on which children from schools across the world have been invited to doodle, as if drawing on their desks like generations of children before them. Displayed flat on table-tops, they reveal the preoccupations of children in very different countries, cities and contexts.

These historical artefacts are given added poignancy and power through their proximity to another installation encouraging, prioritising and revealing children’s ways of seeing. Frequencies by Colombian artist Oscar Murillo – who is currently nominated for the Turner Prize – brings together canvases on which children from schools across the world have been invited to doodle, as if drawing on their desks like generations of children before them. Displayed flat on table-tops, they reveal the preoccupations of children in very different countries, cities and contexts. Another complementary exhibition Transformations: Cloth & Clay at the National Arts Education Archive explores tensions between crafts and design, changing ideas about what these mean, and how they interacted with developments in the ways in which art was taught in schools, universities and experimental establishments such as Dartington Hall across the twentieth century.

Another complementary exhibition Transformations: Cloth & Clay at the National Arts Education Archive explores tensions between crafts and design, changing ideas about what these mean, and how they interacted with developments in the ways in which art was taught in schools, universities and experimental establishments such as Dartington Hall across the twentieth century.

What became clear to me across both Ewan’s installation and the NAEA exhibition was how many individuals were pioneering creative approaches to learning in post-war schools, and how much more I have to read, learn and think about.

Asking Out is at the Longside Gallery, Yorkshire Sculpture Park until Saturday 3 November: https://ysp.org.uk/exhibitions/ruth-ewan-and-oscar-murillo

Transformations: Cloth & Clay is at the National Arts Education Archive, Yorkshire Sculpture Park until Saturday 3 November: https://ysp.org.uk/exhibitions/transformations-cloth-and-clay