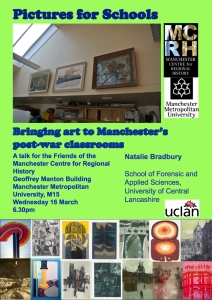

Pictures for Schools in the modernist magazine

Posted: March 11, 2016 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: art, art education, Manchester, Painters, painting, Pictures for Schools, post-war 1 Comment I have written an article about my Pictures for Schools research for the latest edition of the modernist magazine, which focuses on twentieth century architecture and design. As the issue is themed ‘Forgotten’, I have discussed Pictures for Schools as a forgotten idea and ideal which was once successful and well-regarded but today is all but unknown.

I have written an article about my Pictures for Schools research for the latest edition of the modernist magazine, which focuses on twentieth century architecture and design. As the issue is themed ‘Forgotten’, I have discussed Pictures for Schools as a forgotten idea and ideal which was once successful and well-regarded but today is all but unknown.

For more information, and to purchase the magazine, visit www.the-modernist.org/forgotten.

Exhibition visit: ‘Elisabeth Frink: The Presence of Sculpture’, Nottingham Lakeside Arts

Posted: February 24, 2016 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: art, Coventry, Coventry Cathedral, drawings, Elisabeth Frink, exhibitions, Manchester, Nottingham, Pictures for Schools, post-war, public art, sculpture 2 Comments I was delighted to stumble across an exhibition of sculptures by Elisabeth Frink during a daytrip to Nottingham at the weekend, at the university’s Lakeside gallery. Frink was one of the best-known British artists to be involved in the Pictures for Schools exhibitions, and served on selection committees to select sculptures for the exhibitions for a number of years. She also submitted sculptures to Pictures for Schools, and sold works on paper through the scheme, including drawings from her Spinning Man series.

I was delighted to stumble across an exhibition of sculptures by Elisabeth Frink during a daytrip to Nottingham at the weekend, at the university’s Lakeside gallery. Frink was one of the best-known British artists to be involved in the Pictures for Schools exhibitions, and served on selection committees to select sculptures for the exhibitions for a number of years. She also submitted sculptures to Pictures for Schools, and sold works on paper through the scheme, including drawings from her Spinning Man series.

Entitled ‘The Presence of Sculpture’, the Nottingham show focused largely on Frink’s post-war commissions and drew attention to themes and subject matter, from heads (many displaying a smooth serenity), horses and birds to movement, change, uncertainty and the lightness and heaviness of flight. Works and studies on display included large-scale sculptures for corporate companies such as WH Smith, and work in the Battersea outdoor sculpture exhibition, as well as religious and public commissions, including her angular, roughly textured eagle lectern for Coventry cathedral and her controversial tribute at Manchester airport to Alcock and Brown’s non-stop Atlantic flight, which somehow manages to retain a sense of grace despite the flailing, tapering descent of the legs and the contrast between the smoothness of the man-made wings and the awkwardness of the human body. Much was made of the ways in which her artworks were encountered in people’s everyday lives.

Entitled ‘The Presence of Sculpture’, the Nottingham show focused largely on Frink’s post-war commissions and drew attention to themes and subject matter, from heads (many displaying a smooth serenity), horses and birds to movement, change, uncertainty and the lightness and heaviness of flight. Works and studies on display included large-scale sculptures for corporate companies such as WH Smith, and work in the Battersea outdoor sculpture exhibition, as well as religious and public commissions, including her angular, roughly textured eagle lectern for Coventry cathedral and her controversial tribute at Manchester airport to Alcock and Brown’s non-stop Atlantic flight, which somehow manages to retain a sense of grace despite the flailing, tapering descent of the legs and the contrast between the smoothness of the man-made wings and the awkwardness of the human body. Much was made of the ways in which her artworks were encountered in people’s everyday lives.

However, my favourite works were those depicting boars, including a spindly-tailed bronze in which the bulk of the animal has been arrested in movement, seemingly coming to a sudden stop. I also loved the washed-out colour and hairy detail of the 1967 lithograph ‘Wild Boar’.

However, my favourite works were those depicting boars, including a spindly-tailed bronze in which the bulk of the animal has been arrested in movement, seemingly coming to a sudden stop. I also loved the washed-out colour and hairy detail of the 1967 lithograph ‘Wild Boar’.

‘The Presence of Sculpture’ finishes on Sunday February 28.

Exhibition visit: We Want People Who Can Draw: Instruction and Dissent in the British Art School, Manchester Metropolitan University Special Collections (until 31 July)

Posted: July 16, 2015 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: archives, art, art education, Art school, dissent, Education, Exhibition catalogue, exhibitions, Hornsey, Manchester, Manchester Metropolitan University, occupations, post-war, protest, universities Leave a commentThough it’s not directly related to schools, as part of the contextual reading for my PhD I have also read a lot about the history and development of art education, specifically art schools and colleges in Britain, from the municipal colleges of art that were set up in industrial towns and cities in the nineteenth century, to the changing status of provincial schools of art and art degrees following the Coldstream Report of 1960, to the student protests and occupations sparked by that at Hornsey in 1968, where students demanded more say in the direction of their education.

The current exhibition at Manchester Metropolitan University’s Special Collections brings together an impressive, stimulating and inspiring range of materials relating to the last of these aspects of the history of British art education, borrowed from individuals and institutions including the Women’s Art Library in London. They encompass manifestos, books, magazines, pamphlets and student journals, including material from Art & Language in Coventry and King Mob at Goldsmiths in London, along with exhibition publicity, films, some evocative photographs of demonstrations and occupations, and prints and posters relating to these demonstrations, and correspondence between students and university officials. Through these artefacts, the exhibition draws out links with wider and international movements for change such as the Situationist International and radical feminism. Many of the publications were amassed and distributed by Ron Hunt, the librarian at Newcastle University, who must have some tales to tell!

Many of the objects, as well as being fascinating documents of the time and a particular educational and social moment, raised important questions about the purpose and uses of art in the post-war context, a period in which the government and other authorities had started by promoting the potential and responsibility of art to take on an explicitly social role in both educating and improving the lives and leisure of the masses. Should art, and the critical and technical skills students developed at art schools, be used for the good of society, as in the street theatre workshops discussed in the exhibition, or should it be enlisted into the commercial services of advertising, against which students at Hornsey were partly protesting? One of the most intriguing items in this regard was Ken Garland’s 1964 First Things First manifesto, recently updated fifty years on, which enlisted the signatures of several designers to rail against advertising and call for design which worked for the public good. It would be interesting to know what came of the signatories, and where their future careers led them …

At a time when the value – and cost – of studying arts subjects, not just at school but at degree level, is being questioned, and when university buildings are still being occupied through student protests, it was strange not to see present-day imagery and examples in the exhibition, despite this providing the starting point for the exhibition catalogue.

The catalogue is well worth a read and is accessible as PDF at www.specialcollections.mmu.ac.uk/files/wewantpeople_guide.pdf.

Final visit to Nan Youngman collection, University of Reading

Posted: September 27, 2014 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: archives, Cambridgeshire, Derbyshire, Hertfordshire, Leeds Art Gallery, Leicestershire, loan collections, Manchester, Manchester Art Gallery, Nan Youngman, Peter Green, Pictures for Schools, Pictures for Welsh Schools, prints, school loans services, University of Reading, West Riding 8 CommentsThis week I made my fourth and final visit to see Nan Youngman’s papers at the University of Reading. It felt very much like a finishing up and plugging the gaps visit, and I know feel like I’ve looked at everything in the collection and seen the full scope of what’s there. I found out about some more minor details of the Pictures for Schools exhibitions such as how they were publicised – this included advertising at underground stations, and writing to London borough libraries to ask them to display leaflets.

One of the things I got from the trip was a real sense of who the educational buyers were from Pictures for Schools, and what types of artworks and which artists were particularly popular, through looking at a series of invoice books from 1949 to 1968 (although there are some gaps where invoice books are missing, including a long period in the 1950s).

Schools of all kinds, including secondary moderns, grammars, junior schools and independent schools purchased work from Pictures for Schools, sometimes on a one-off basis and sometimes as repeat buyers, with Manchester Grammar School being a particularly regular buyer (this interested me as Mrs Rutherston was frustrated that it failed to make use of Manchester Art Gallery’s Rutherston Loan Scheme, and seemed generally unimpressed with the quality of art teaching at the school). Other regular buyers included Greenwich Library in the 1960s, as well as various training colleges around the country, and occasionally adult, further and higher education establishments. Other buyers included county or city loan services linked with museums, including Reading Museum and Art Gallery (this service is still in operation and embroideries by artists including Constance Howard and Sadie Allen purchased through Pictures for Schools in the 1960s are still available for schools to borrow), Ferens Art Gallery, who made purchases on behalf of Hull Education Committee and the Leeds Loan Collection which was linked both with Leeds College of Art and Leeds Art Gallery.

Although, as I already knew, Derbyshire Museum Service made regular and extensive purchases, I revised my opinion a little about the number of local authorities making use of the scheme, who seem to be slightly less numerous and widespread than I thought, although Essex County Council, Kent, Cambridgeshire, Great Yarmouth, Cumberland/Carlisle, Northumberland/Newcastle, Lancashire, City of Coventry, Cambridgeshire/City of Cambridge, West Bromwich, City of Manchester, Shropshire, Worcestershire, Buckinghamshire, Oxford, Rochdale, the London County Council and later Nottingham and Scunthorpe and Bromley were enthusiastic and regular buyers from the scheme, with West Sussex, East Sussex, Norfolk, Bristol, Somerset, Devon, Dorset, East Yorkshire, Gloucester, Southampton, Bradford, Croydon, Kingston upon Thames, Rotherham, Birmingham and Harrow Schools Art Library making purchases more intermittently. I also realised I may have overstated the links between Pictures for Schools and counties such as the West Riding, Hertfordshire and Leicestershire, who I know to have had extensive loan collections and to have valued art in schools. Whilst they did certainly support Pictures for Schools in its early years, they appear to have stopped being regular purchasers by the late-1950s and 1960s, perhaps because they had become accustomed to buying art on a more year-round basis and approaching and liaising with artists and galleries direct. Educational buyers from Wales (and very occasionally Scotland) also made occasional purchases, although Wales had its own Pictures for Welsh Schools exhibitions from 1951 and a one-off Pictures for Scottish Schools exhibition was held in 1967. One thing I am interested in finding out more about are the art advisers who visited Pictures for Schools on behalf of county education committees, some of whom seem to have had interesting artistic careers and involvement in their own right, including Robert Washington, long-running art advisor for Essex.

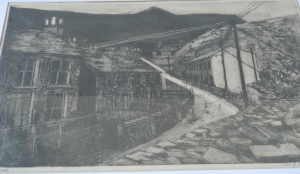

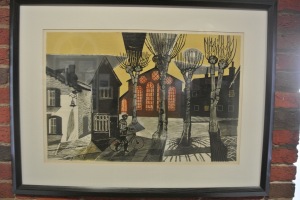

I noticed that prints were by far the most popular item, probably due to their affordability (many buyers purchased prints unframed) with embroidery also popular and sculpture noticeably unpopular. One name which really stood out was the print-maker Peter Green, who seemed to make extensive sales at each exhibition, as did fellow print-makers Philip Greenwood, Michael Stokoe and Richard Tavener. Something else I noticed was that buyers often stuck with one artist and continued to collect their work year on year. As I’d observed previously, I also came across more correspondence from schools and local authorities which had purchased work from artists and wished to follow up by contacting the artists to ask for biographical or other information to complement the use of the works as learning resources, and sometimes to arrange local exhibitions of particular artists’ work.

Nan Youngman painting in Manchester Art Gallery

Posted: June 9, 2014 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: art, Manchester, Manchester Art Gallery, Nan Youngman, painting Leave a commentDuring my visit to Manchester Art Gallery last week I was pleased to be told that an oil painting by Pictures for Schools founder Nan Youngman, entitled Convolvulus (1943), will soon be going on display in the Art Gallery cafe. I enjoyed having a chance to view the painting in the store, a still-life in a striking colour palette of red, white and green, as previously the paintings I had seen by Youngman comprised landscapes and a self-portrait.

Convolvulus is one of two Nan Youngman paintings in the collection, the other being Waste Land, Tredegar, South Wales (1951), which stands out to me among Youngman’s output I have seen for its human element: there’s a lot of movement to the painting, in contrast with the deserted stillness I associate with many of Youngman’s paintings of deserted buildings, streetscapes and imposing landscapes. The painting is populated by the soft-edged outlines of small children busy at play, in groups and as individuals, foregrounded in colour against the griminess of a polluted industrial backdrop. However, the staff I spoke to didn’t seem to know much about Youngman and her history beyond her association with Cambridge.

Manchester Art Gallery’s Rutherston Loan Scheme

Posted: June 9, 2014 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: archives, art, Elisabeth Frink, loan collections, Manchester, Manchester Art Gallery, Nan Youngman, painting, Pictures for Schools, research, sculpture 9 CommentsLast week I finally had chance to follow up a reference from my last visit to the Nan Youngman collection in Reading: a trail of correspondence between the organisers of Pictures for Schools and the keepers of the Rutherston Loan Scheme at Manchester Art Gallery. The correspondence dated back to the 1960s, when Keepers of the Rutherston scheme were visitors to the Pictures for Schools exhibitions in London each year and made a number of purchases of sculptures, drawings, paintings and prints. At the exhibitions, the Keeper made a list of reserved artworks which, if they were not sold to schools or education authorities first, were sent to Manchester to be approved for purchase for the collection by a council committee.

The Rutherston Loan Scheme was aimed at educational institutions and art galleries in the North of England. I am curious to find out what happened to some of the artworks and how they were used once they left Pictures for Schools, yet I could find very little reference to the scheme on the art gallery’s website. I made an enquiry about whether the scheme and collection was still in existence, and what kind of records existed relating to its history and was informed that the scheme ran until the late-1970s, when a public aspect was introduced to the scheme, with local ratepayers able to borrow works for their homes. Later, in the 1980s, the scheme became a community scheme with exhibitions lent to schools and community centres. The scheme finally came to an end in the early-’90s, following rate caps and a resultant reduction in staffing levels, and artworks were accessioned into the main collection. Like many other instances of loan collections, insurance too was increasingly problematic. Today, the gallery has corporate loan schemes, which lend work suitable for the offices of local firms such as barristers’ offices. New work is acquired for this collection, often by young talent, which can later be accessioned into the main collection. Following an exhibition about nineteenth century philanthropist and Ancoats museum founder Thomas Horsfall, which worked alongside a local primary, it is encouraging to hear that artworks will once again be going into schools.

Manchester Art Gallery gallery has a useful set of records relating to the Rutherston Loan Scheme, dating back to the 1920s when the collection was founded by Bradford businessman and art collector Charles Rutherston. A transcript of a speech made at Manchester Art Gallery in 1926 reveals that after searching for a place to house his collection, he settled on Manchester due to the need for the provinces to have access to art, the good example set by existing levels of cultural provision in the city, and a pre-existing relationship with curator Lawrence Haward and his interest in modern layouts for art galleries. Manchester was also chosen because of its relative proximity to Rutherston’s home city of Bradford, which would enable circulation to institutions across Lancashire and Yorkshire. Rutherston considered it to be important that the collection could be circulated rather than having a permanent home at one gallery, acting as an educational aid, and initially anticipated that schools of art would be the most regular borrowers (it turned out that secondary schools in fact made most use of the scheme). The Arts Council later picked up on this, and circulated the collection regionally to stimulate interest in similar schemes in other parts of the country.

The pilot version of the scheme loaned artworks for one year, although this was felt to be too long to maintain students’ interest and termly loans were initiated instead. The scheme worked by lending groups of pictures to borrowers, either grouped by artistic theme or by ‘different methods of approach to artistic problems’, which could be supplemented from a pool of pictures. Borrowers could visit the collection to make a choice for themselves, or the Keeper could make a choice on their behalf, and the Keeper was also available for illustrated talks. Borrowers had to pay for transport by road or rail, and insurance arranged at ‘reasonable rates’ through the Manchester Corporation. The art gallery has lists of local schools which made use of the scheme, as well as annual reports, which reveal that the scheme was used extensively by elementary and secondary schools throughout Manchester and Salford, along with those in towns in the surrounding area such as Warrington and Bury, as well as specialist schools such as a school in the countryside for epileptics and an experimental boarding school near Clitheroe for children from Salford where students would otherwise have had little opportunity of seeing art. Schools of art made use of loans by displaying examples of work from the collection in the dedicated studios in which that medium was taught – for example, figurative work was shown in the life drawing room. Exhibitions of selections from the collection were also held at Platt Hall, the art gallery’s south Manchester outpost in Fallowfield.

Rutherston was first inspired to collect art by his brother, the painter Will Rothenstein, and, through Will, become part of a social circle that included members of the New English Art Club. This group was drawn on heavily for the collection, along with other groups of artists such as the London Group and the Camden Town Group. Although Rutherson also collected examples of ‘ancient Oriental Pottery, Bronzes and Carvings’, and the collection contained a few examples of foreign artists, his aim was the ‘cultivation of the Modern School of English Art’. In this way, like Pictures for Schools, the scheme offered support for young and unrecognised artists alongside more established names (albeit supplemented by reproductions of masterpieces if it was found to be necessary). The acquisition of work by living artists continued throughout the collection’s existence, with an emphasis on the modern, contemporary and progressive, and the collection aimed to provide a wide survey of twentieth century art and the ‘modern outlook’, aiming to stimulate interest in ‘new forms of visual expression’ among borrowers. Rutherston saw his gift as the ‘nucleus’ of a collection which would grow with gifts and further acquisitions, and a number of donations came from the Contemporary Art Society. Other artworks were purchased at exhibitions of local artists. During the Second World War, the Rutherston Scheme had links with CEMA (the Council for the Encouragement of Music and Art), and works were acquired from the War Artists’ Advisory Council. Other works in the collection were humbler forms, such as linocuts, which were thought to be of particular interest to schools as students often made linocuts in art classes.

I was able to view a few of the works which were purchased through Pictures for Schools in the 1960s in the art gallery’s store. Although sculpture is stored elsewhere in Manchester (the curator mentioned that much of the gallery’s post-war sculpture is small in scale, something which fits in with my observations of the sculpture in the Derbyshire County Council school loan collection), I was able to view an extraordinary (yet probably slightly disturbing for schoolchildren) drawing by Elisabeth Frink, Bird Man (1963), which depicts movement through an unusual drawing technique and diagonal composition. Another artwork, Studies in Line (1964), a print by Conrad Atkinson, appeared to be a snapshot of an endless variation of experiments into the possibilities of line and form which drew the eye back again and again. An artwork by Pauline Smith, Museum Study (1968), was a real curiosity, a proscenium arch drawn on graph paper in the luminous oranges and purples characteristic of the era. Unframed, it appeared to be more of a study or demonstration exercise to be shown to students than something designed to beautify a wall. One of the artworks purchased through Pictures for Schools, however, is currently on loan to the office of Sir Richard Leese, leader of Manchester City Council.

One of the most interesting chapters of the Rutherston collection’s history relates to the Second World War and the continuing importance of the arts at that time. Despite difficulties such as transport limitations, the evacuation of Manchester schools and the storage of some of the more valuable works safely away from Manchester, the collection was in high demand and schools continued to make good use of artworks even in temporary accommodation. Loans from the collection were also distributed to YMCAs, service camps, factory hostels, hospitals, factories and local firms, as well as the local Juvenile Employment Bureau where children discussed the pictures informally amongst themselves whilst waiting to be seen.

Another interesting aspect to the scheme was the lively interest taken by Rutherston’s widow, Essil R. Elmslie (1880–1952), an artist and owner of the Redfern Gallery in London, after his death in 1927. A steady stream of correspondence between Mrs Rutherston and the Keeper of the collection reveals that she made regular visits to Manchester, and was keen to visit schools and other borrowers to see how they were making use of the collection (as well as trying to encourage those schools which weren’t making use of the collection, such as Manchester Grammar, where paintings were only displayed in the Masters’ areas, to do so, and giving suggestions for schools which felt they had nowhere to display artwork). Mrs Rutherston made regular purchases for the scheme, both from gallery exhibitions as well as student potters at the school of art local to her in Farnham.

Along with the artworks purchased from Pictures for Schools for the Rutherston Loan Scheme, there are other interesting links between the schemes. ‘Rutherston’ was an anglicised version of the surname ‘Rothenstein’, and Charles Rutherston was the uncle of John Rothenstein, director of the Tate Gallery from 1938-1964, who was involved in selecting artworks for early instalments of Pictures for Schools. Youngman also knew John Rothenstein’s brother, the painter Michael Rothenstein, socially as part of a group of East Anglian painters. Another possible link with Nan Youngman is through the Society for Education in Art, under whose name Pictures for Schools was organised: Mrs Rutherston was actively involved in the local branch at Farnham in Surrey, helping to organise a wartime exhibition in aid of the Red Cross, and wrote with enthusiasm about attending an SEA conference at Somerville College, Oxford, addressed by Herbert Read and the art critic Eric Newton (a Manchester man who wrote regularly about Pictures for Schools in the press), where she tried to spread the word about the Rutherston Loan Scheme among those she met.

It is hoped that there will eventually be an exhibition of work from the Rutherston Loan Collection at Manchester Art Gallery, which I think is a great idea given its long and fascinating history.

works of art purchased by the school can be found among this, and highlights of the collection are on display in a wide corridor area. These include Edwin La Dell’s 1960 lithograph ‘Priddy Nine Barrows’, a green, rolling rural landscape. Though I had seen photographs of the print before, I much preferred it in ‘real life’, seeing its mark-making close-up and its colour choices appearing more vibrant.

works of art purchased by the school can be found among this, and highlights of the collection are on display in a wide corridor area. These include Edwin La Dell’s 1960 lithograph ‘Priddy Nine Barrows’, a green, rolling rural landscape. Though I had seen photographs of the print before, I much preferred it in ‘real life’, seeing its mark-making close-up and its colour choices appearing more vibrant.

The round, light-filled Chapel of Christ the Servant, with its floor-to-ceiling windows, on the other hand, looks out onto the brutalist architecture of Coventry university, including a high-rise accommodation block, though the modernist campus is effectively landscaped with green space.

The round, light-filled Chapel of Christ the Servant, with its floor-to-ceiling windows, on the other hand, looks out onto the brutalist architecture of Coventry university, including a high-rise accommodation block, though the modernist campus is effectively landscaped with green space.